May 6, 2010 feature

'Smart' wound dressings could identify and destroy infection-causing bacteria

(PhysOrg.com) -- Although bacterial infection as a clinical problem was reportedly defeated with the widespread use of antibiotics in the 1950s, its re-emergence over the last few decades has persuaded researchers to develop new methods for killing and preventing the growth of pathogenic bacteria. In a new study, a team of chemists from the University of Bath, UK, have taken steps to engineer a "smart" wound dressing system that releases an encapsulated antimicrobial agent only in the presence of pathogenic bacteria, allowing the body’s normal microflora to continue providing a natural defense against infection.

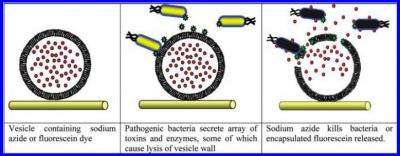

The prototype wound dressing is made of a nonwoven polypropylene fabric. Attached to the fabric are vesicles containing an antibacterial agent. One of the virulence factors of many pathogenic bacteria (but not nonpathogenic bacteria) is that they secrete toxins or enzymes that damage vesicle membranes by lysing (bursting) them. When the pathogenic bacteria lyse the membranes of the vesicles attached to the smart fabric, the vesicles rupture, releasing the antibacterial agent and destroying the bacteria. In this way, the vesicle system can be thought of as a “Trojan horse,” inciting pathogenic bacteria to act as agents of their own destruction.

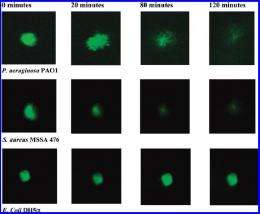

In their experiments, the researchers took samples of a viable bacterial population of two species (Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) every 20 minutes for four hours following exposure to the smart fabric. They observed significant decreases in the concentrations of both species, and eventually nearly complete inhibition. The researchers also found that concentrations of P. aeruginosa declined at a faster rate than S. aureus due to P. aeruginosa’s greater sensitivity to the encapsulated antimicrobial agent

Further, the researchers observed that, in uninfected samples that contained only non-pathogenic Escherichia coli, concentrations of the E. coli were only slightly reduced, which likely resulted from minor leakage of the vesicles. By ensuring that the antibacterial agent is released only in the presence of pathogenic bacteria, the strategy minimizes evolutionary pressure for the selection of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, prolonging the effectiveness of the antibacterial agent.

“The potential significance of this work is that we have a proof-of-principle of a ‘smart’ system which is able to discriminate between pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria,” coauthor Toby Jenkins of the University of Bath told PhysOrg.com. “The advantage of this in a wound dressing is that it will only release an antimicrobial if the wound becomes infected with dangerous bacteria, but won’t respond to harmless commensal bacteria which may be present. This reduces the evolutionary selection pressure on bacteria of all types to evolve resistance and should slow the emergence of new antibiotic resistant species of bacteria such as MRSA.”

In addition to controlling bacterial growth and infection, the researchers intend to enable the smart fabric to change color on infected wounds. They explain that a simple colorimetric or fluorometric response could be built into the fabric, giving patients and clinicians early warning of wound infection.

“From a clinical perspective, especially in the treatment of pediatric burns, there is an enormous advantage in being able to leave a dressing in situ for as long as possible following a burn, as this promotes healing, reduces trauma and ultimately saves money,” Jenkins said.

Overall, the researchers have shown that one of the very features that makes some bacteria pathogenic - the ability to damage cell membranes - can be used against them. However, before the smart fabric can be commercially produced, the researchers still must find solutions to several problems, including vesicle stability, tuning of response, and manufacturability, among others.

“We hope to have a full working prototype, with a clear pathway to manufacturability by 2014,” Jenkins said. “We envisage a further three to four years of safety and compliance testing, so 2017 is probably the earliest realistic target for coming to market.”

Still, as Jenkins explained, no matter how advanced such technology becomes, it will not be possible to fully eliminate the threat of clinical bacterial infection, as thought in the ‘50s. Instead, the battle will be an ongoing one.

“The process of evolution by natural selection - the process by which we evolved and bacteria evolve antibiotic resistance - is too powerful a force [to allow antibacterial agents to eliminate pathogenic bacterial infection],” he said. “But we can try to be clever, understand better how this process works, and try to stay one step ahead of Nature.”

More information: Jin Zhou, Andrew L. Loftus, Geraldine Mulley, and A. Toby A. Jenkins. “A Thin Film Detection/Response System for Pathogenic Bacteria.” J. Am. Chem. Soc. Doi:10.1021/ja101554a

Copyright 2010 PhysOrg.com.

All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of PhysOrg.com.