Rosetta: The end of a space odyssey

Europe's trailblazing deep-space comet exploration for clues to the origins of the Solar System ends Friday with the Rosetta orbiter joining robot lab Philae on the iceball's dusty surface for eternity.

The 1.4-billion-euro ($1.5-billion), 12-year odyssey will conclude with a last-gasp spurt of science-gathering as Rosetta departs the orbit of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko and descends over 14 hours to her final resting place.

Despite the looming end of a mission that has been formative for many of their careers, European Space Agency (ESA) scientists are looking forward to this final phase of sniffing, tasting and photographing "67P" from just a few hundred, perhaps tens, of metres (yards) away.

After despatching the final data to Earth, Rosetta's signal will simply vanish from ground control screens at about 1120 GMT, likely with partly-uploaded data still in the system.

It takes 40 minutes for Rosetta's signal to arrive at mission control in Darmstadt, Germany, meaning its actual time of death will be around 1040 GMT.

"It will basically all just disappear in one go, and that'll be it. There will be nothing else," said ESA senior science advisor Mark McCaughrean.

Read also:

Rosetta: How to end the fairytale

Rosetta: What did Europe's comet mission uncover?

The first-ever mission to orbit and land on a comet was approved in 1993 to explore the origins and evolution of our planetary system—of which comets are thought to contain prehistoric elements preserved in a dark space deepfreeze.

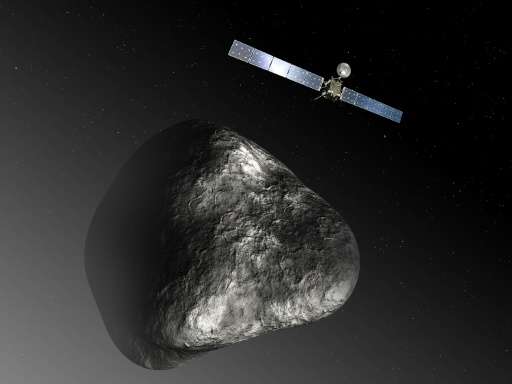

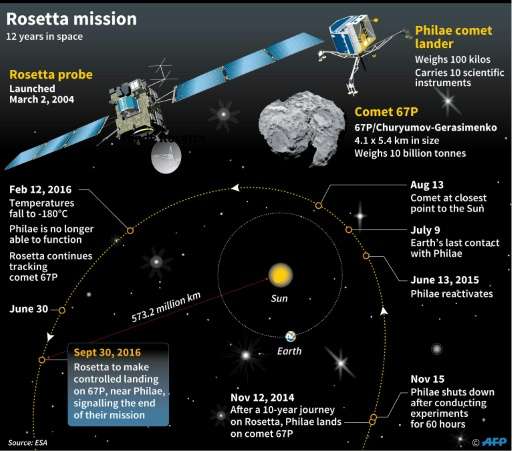

Rosetta and comet lander Philae blasted off in March 2004, travelling more than six billion kilometres (3.7 billion miles) to reach the comet in August 2014, aided by slingshot gravity boosts on flybys of Earth and Mars along the way.

The comet chaser and Philae, which it placed on the surface in November 2014, have demystified some aspects of comets as well as adding to their enigmatic allure.

Measurements taken by the pair revealed that comets crashing into an early Earth may well have brought amino acids, the building blocks of life.

Comets of 67P's type, however, definitely did not bring water, yet inexplicably contained oxygen, scientists concluded.

Controlled impact

At this moment, the comet, with Rosetta in tow, is moving further and further away from the Sun, having made the closest solar pass on its 6.6-year elongated orbit in August 2015.

This means the orbiter's solar panels are catching fewer and fewer battery-replenishing rays.

Ground controllers faced a difficult decision—keep Rosetta in orbit to try and make contact the next time it draws near the Sun, or sacrifice the craft for a close-up inspection?

Rosetta was never designed to land, and it was not sure to survive another loop around the Sun.

So scientists opted for "controlled impact" with Rosetta joining the already-spent Philae, its constant companion for the last two years, on the comet's surface—though on the opposite side.

On its descent, the plan is for Rosetta to peer into mysterious pits dotting the comet landscape for hints as to what the body's interior might look like.

"It's a very, very exciting part of the mission, maybe one of the most exciting parts," Rosetta team member Claire Vallat said.

The closest Rosetta had ever been to the surface was about 1.9 km.

Final manoeuvres will take place during the night of September 29, with the comet more than 700 million km from Earth and travelling at a speed of over 14 km/second.

About 20 km from the comet, Rosetta will be instructed to break its orbit and make a 90-degree turn, heading in a straight line for 67P.

It will also be programmed to shut down on impact, so as not to pollute any deep space radio frequencies for future missions.

Rosetta is meant to reach the surface at a human walking-speed of about 90 centimetres per second (35 inches per second).

Time capsules

"It will not be a crash," flight operations manager Andrea Accomazzo stressed, though instruments and solar panels will inevitably be damaged.

"For sure, Rosetta will sort of bounce and tumble on the surface of the comet. It will not stick immediately to the surface of the comet, but it will not bounce back into orbit."

Once the craft is down, there would be "absolutely no chance to communicate with her anymore," said Accomazzo. Rosetta's main antenna needs be out by a mere 0.5 degrees in order not to work.

The bold mission to probe a prehistoric time capsule had captivated the imagination of adults and children worldwide, partly thanks to a cartoon video series representing the pair as an amiable sister-brother pair on an epic and perilous adventure.

"We've had people tell us... this is their Apollo moment," McCaughrean said, referring to the 1969 Moonlanding watched in black-and-white on televisions around the world.

Some of the science teams involved have invested more than 20 years in Rosetta.

Fabio Favata of ESA's robotic exploration directorate, said he worried for them about the "the down that will come once this is over, because I think they've been living on adrenaline for quite some time."

"It is my third child," said Sylvain Lodiot, spacecraft operations manager.

But all is not lost.

"The mission is much more than just the spacecraft. We'll have data collected that we will have to exploit for decades," said Accomazzo.

—-

Rosetta's 7-billion-kilometre space mission

European spacecraft Rosetta will end its mission on September 30 after travelling almost seven billion kilometres (4.4 billion miles) to probe the secrets of comets, with help from a high-tech robot named Philae.

The 1.4-billion-euro ($1.6-billion) project has spanned 23 years and involved 14 European countries, as well as the United States.

A chronology:

Blastoff

Rosetta and Philae blasted off from the Kourou launch centre in March 2004, the culmination of a ten-year development programme by the European Space Agency (ESA).

The goal of the mission was nothing less than probing the origins of life by analysing dust from a comet called 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, a time capsule from the birth of our solar system.

In the comet's orbit for more than two years, Rosetta sniffed, tasted and photographed the comet from all angles.

And it released Philae, the size and shape of a washing machine, onto the surface to analyse elements and send data to Rosetta for relay back to Earth.

Rosetta used the gravity of Earth and Mars to slingshot four times—in a game of cosmic billiards—towards the Sun.

On its ten-year journey to the comet, the probe passed Earth three times (2005, 2007 and 2009), and flew by Mars once in 2007.

Nap time

After more than seven years of travel, Rosetta found itself some 800 million kilometres (500 million miles) from the Sun, its rechargeable batteries fading.

The spacecraft went into "hibernation" to conserve energy in June 2011, when it was about one billion kilometres (620 million miles) from Earth.

After 957 days in this artificial coma, Rosetta was woken up in January 2014 for its rendezvous with "67P".

It entered the comet's orbit in August that year after a six-billion-kilometre (3.7-billion-mile), decade-long trek.

Hard landing

On November 12, 2014, Philae made a historic landing on the comet. But its harpoons failed to fire, causing it to bounce several times and end up in a ditch, hidden from the Sun's battery-replenishing rays. Ground control could not pinpoint its exact location.

But Philae's 10 instruments managed to work for around 60 hours, providing scientists with unprecedented data before entering standby mode.

In June 2015, the robot-lab surprised ground control crews with an unexpected message: "Hello Earth! Can you hear me?".

Last contact was on July 9, 2015.

Front-row seat

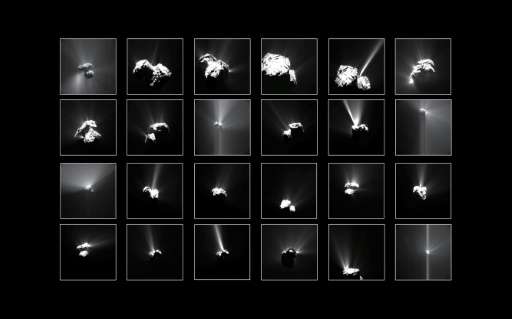

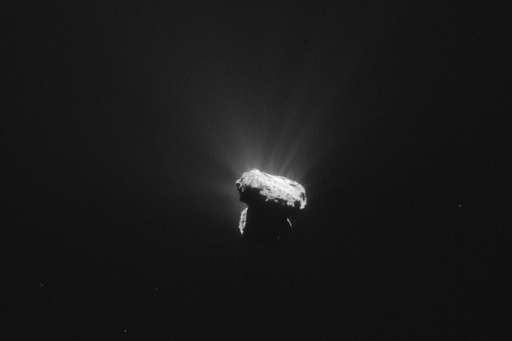

In August 2015, the comet came within 186 million kilometres (115 million miles) of the Sun, its closest point. Rosetta had a front-row seat for the spectacular plumes of gas and dust that comets typically generate when they get close to white-hot stars.

Philae refound

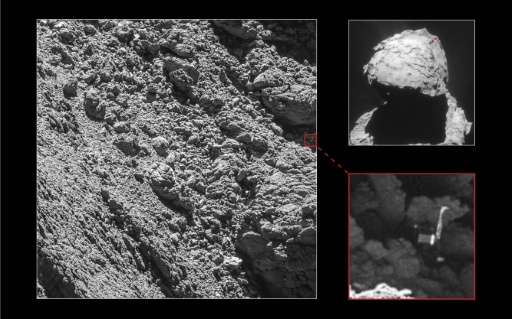

On September 2, 2016, Rosetta was about a month from the scheduled end of its mission when a camera spotted Philae—still on the comet—"at the foot of a cliff in an extremely rocky zone," in the words of project chief Philippe Gaudon.

After bouncing, the photo showed, the probe had came to a stop "with one foot in the air" and its antennae pointing into the ground.

The ESA decided to let Rosetta crashland nearby on September 30, reuniting the intrepid duo forever in a fitting end to their historic mission.

——

After Rosetta: What are the next frontiers?

After Europe terminates its Rosetta mission—the world's first-ever orbit and landing on a comet zipping through space—what can we look forward to next in the exploration of faraway frontiers?

Moon village

Dismissed as "crazy" by some, the European Space Agency's new boss hopes to pioneer a research village on the Moon—a multinational project to replace the International Space Station which is currently envisioned to operate until 2024.

Jan Woerner has put his proposal, though still in its infancy, to the bosses of other space agencies, seeking a joining of forces to build a base for lunar exploration by humans and robots, and possibly even a mining site.

Such a base could also serve as a stopover for spacecraft to and from destinations further afield, such as Mars.

Catching an asteroid

NASA has ambitious plans to capture a boulder from an asteroid and move it into orbit around the Earth's Moon for close-up study.

Once there, the American agency plans to send two astronauts to collect samples from the boulder wearing spacesuits designed for deep space missions.

This would help prepare for future missions to obtain, and return, samples from Mars, for example.

Earlier this month, an American spacecraft called OSIRIS-REx set off to collect samples from an asteroid, which like comets are thought to have delivered life-giving materials to a juvenile Earth.

They are believed to contain material from the birth of the Solar System.

Added to data gathered by Rosetta and comet lander Philae, further asteroid analysis may help piece together the origins and evolution of our planet and its neighbours.

Efforts to deflect incoming asteroids which threaten to impact Earth, are still in the conceptual phase.

The Red Planet

The next mission to probe Mars for traces of life will be the joint Europe-Russia ExoMars rover due for launch in 2020. It will be built to drill up to two metres (seven feet) into the martian surface.

An ExoMars orbiter will arrive at the Red Planet in October to analyse its atmosphere and place a trial lander dubbed Schiaparelli on its surface.

NASA's Curiosity rover has already been criss-crossing our neighbour planet for more than three years.

The American agency has plans for a manned trip to Mars in the next 10-15 years, with similar a project also being pursued by US billionaire Elon Musk.

Dutch company Mars One, hopes to create human colonies on the Red Planet, and is running Earth-based experiments in preparation, with volunteers.

For the moment, return is not part of the plan.

More information:

Read also:

Rosetta: How to end the fairytale

Rosetta: What did Europe's comet mission uncover?

© 2016 AFP